Low Back Pain case study: Part 1 - thenakedphysio.com

35 hours ago · Abstract. Low back pain (LBP) is prevalent and may transition into chronic LBP (cLBP) with associated reduced quality of life, pain, and disability. Because cLBP affects a heterogenous population, rehabilitation efforts must be individualized to meet the needs of various patient populations as well as individuals. >> Go To The Portal

Is low back pain a public health burden?

Low back pain (LBP) remains a prevalent health burden according to epidemiological data with an increasing length in years lived with disability (Vos et al., 2012) and an increasing financial burden globally (Hoy et al., 2012).

Is low back pain (LBP) a medical phenomenon?

More recent discussion in the research literature identify LBP as part of a group of enigmatic phenomena classed as medically unexplained symptoms (Eriksen et al., 2013).

What is the prognosis of chronic low back pain?

Conclusions Chronic LBP is a prevalent and surprisingly complex condition that may respond to a range of nonpharmacological treatments. The difficulty in rehabilitation for cLBP is the fact that patient populations are heterogeneous and individualized therapy is appropriate.

Does patient-physician agreement predict outcomes in patients with back pain?

Brief report: Patient-physician agreement as a predictor of outcomes in patients with back pain. J Gen Intern Med2005;20(10):935–7. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How do you describe low back pain?

Dull, aching pain Pain that remains within the low back (axial pain) is usually described as dull and aching rather than burning, stinging, or sharp. This kind of pain can be accompanied by mild or severe muscle spasms, limited mobility, and aches in the hips and pelvis.

How do you describe back strain?

It may be described a number of ways, such as sharp or dull, comes and goes, constant, or throbbing. A muscle strain is a common cause of axial back pain as are facet joints and annular tears in discs. Referred pain. Often characterized as dull and achy, referred pain tends to move around and vary in intensity.

What is low back pain write its symptoms and treatment?

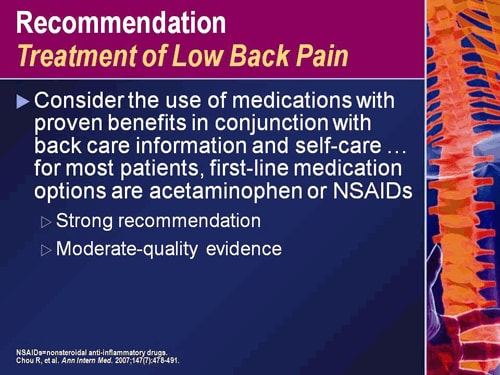

Lower back pain is very common. It can result from a strain (injury) to muscles or tendons in the back. Other causes include arthritis, structural problems and disk injuries. Pain often gets better with rest, physical therapy and medication.

What are some follow up questions that you can ask the patient about their back pain?

15 Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Back PainWhat is causing my back pain?Can some serious conditions be causing my back pain? ... What will worsen my back pain? ... Can stress be a factor? ... What are my treatment options?Are there things I can do at home or in my life to reduce my back pain?More items...•

How do you describe pain?

If you have raw-feeling pain, your skin may seem extremely sore or tender. Sharp: When you feel a sudden, intense spike of pain, that qualifies as “sharp.” Sharp pain may also fit the descriptors cutting and shooting. Stabbing: Like sharp pain, stabbing pain occurs suddenly and intensely.

How would you describe pain to the doctor?

Tell your doctor all of the areas you are experiencing pain. Don't say the pain is in your leg. Explain and point it out to where the specific pain is in your leg. Does the pain transfer to your feet at all?

What is the most common cause of lower back pain?

While every patient's case is unique, the most common causes of lower back pain include: Muscle or Spinal Ligament Strain. A fast movement, repetitive lifting, an awkward bend, or an attempt to lift something beyond your capabilities can all result in a strain that causes severe discomfort.

What are the main causes of back pain?

7 common causes of back painPulled muscle or tendon. Lifting boxes or heavy objects working out and even sleeping in an awkward position can lead to a sore back. ... Inflammation. ... Arthritis. ... Osteoporosis. ... Injured herniated and ruptured discs. ... Stress. ... Fibromyalgia.

Where is lower back pain?

The low back, also called the lumbar region, is the area of the back that starts below the ribcage. Almost everyone has low back pain at some point in life. It's one of the top causes of missed work in the U.S. Fortunately, it often gets better on its own.

How do you document back pain?

Look at the alignment of the spine. Palpation – Palpate the back including the spine and paraspinal region noting areas of tenderness. Range of Motion – Assess and document range of motion of the neck and back including flexion, extension, rotation, and bend.

How do you document pain assessment?

Six Tips to Documenting Patient PainTip 1: Document the SEVERITY level of pain. ... Tip 2: Document what causes VARIABILITY of pain. ... Tip 3: Document the MOVEMENTS of the patient at pain onset. ... Tip 4: Document the LOCATION of pain. ... Tip 5: Document the TIME of pain onset. ... Tip 6: Document your EVALUATION of the pain site.More items...•

How do you evaluate back pain?

If there is reason to suspect that a specific condition is causing your back pain, your doctor might order one or more tests:X-ray. These images show the alignment of your bones and whether you have arthritis or broken bones. ... MRI or CT scans. ... Blood tests. ... Bone scan. ... Nerve studies.

What is manual traction for LBP?

Mechanical and manual traction are old formsof rehabilitation therapy for LBP that have beenfalling out of favor as new treatments emerge.In a systematic review and meta-analysis (32randomized controlled trials, n= 2762) tractionwas found to have little effect on pain intensity,function, global improvement, or ability toreturn to work for patients with LBP. Adverseevents for traction can include worsened pain,neurological symptoms, and subsequent sur-gery [76]. It has been theorized that one reasonfor the relatively poor clinical results fromtraction reported in the literature may be due tothe fact that there are multiple different types oftraction and parameter settings and it is used ina range of patients with back problems [3].Nevertheless, traction is not frequently consid-ered as a treatment for cLBP today.

What is CBT therapy?

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can beeffective in reducing pain, improving dailyfunction, and improving quality of life inpatients with cLBP. Unlike exercise programs orphysical therapy, CBT addresses the psychoso-cial contributors to cLBP. A recent series ofstructured interviews in a prospective extendedcohort (n= 277, 85% response rate) found pos-itive 1-year response rates that were maintainedat 5 years of follow-up [58]. A postmarketingstudy found positive responses to an intensive2-week course of CBT in cLBP patients weredurable at 2 years and patients reported lessconsumption of analgesics [59].

What is low back pain?

Low back pain (LBP) is a prevalentcondition that affects a heterogenouspopulation with varying degrees ofduration (acute versus chronic), severity,pain intensity, and functional limitation.As such, treatments and rehabilitationefforts resist a one-size-fits-all approach.

What are contextual factors?

Contextual factors include patient and clinician sociodemographics, clinician experience and skill, and patient health status and susceptibility to addiction. Contextual factors also include the existing patient-clinician relationship and the nature and purpose of the visit (e.g., emergency department vs primary care).

What is relationship communication?

Relational communication refers to communication that recognizes the centrality of the patient-clinician relationship in providing care. This includes acknowledging the role of these relationships on health and includes communication aimed at fostering autonomy, respect, collaboration, honesty, support, and commitment [78]. Some studies relevant to this component of our model focused on patient displays of emotions. Henry and Eggly [72] found that, when discussing pain, patients display more emotions—both positive and negative—than when discussing other topics. Emotions can be communicated either explicitly or implicitly, and, based on Eide et al.’s [79,80] findings, this difference is associated with different communication patterns. These investigators found that fibromyalgia patients’ implicit references to negative emotions were associated with worse patient-reported health and fewer empathic clinician responses. In contrast, explicit mentions of negative emotions were associated with greater patient-reported negative affect and more empathetic clinician responses.

What is the importance of self-presentation in opioids?

Studies on communication about opioid analgesics also highlighted the importance of self-presentation. For example, Roberts and Kramer described how patients presented themselves to physicians as responsible analgesic users who are just barely managing their pain, thereby showing that they are trustworthy but nevertheless require additional medication [75]. Similarly, Buchbinder et al. [56] used the lens of politeness theory to show how patients worked to present themselves as responsible and deferential medication users worthy of an analgesic prescription.

What is the importance of communication in pain management?

Nearly every aspect of pain management relies on communication: assessing pain and functional status, deciding on pain management goals, implementing treatment plans, and assessing the effectiveness of those plans. The need for clear communication is especially important for noncancer pain. The subjective nature and frequent lack ...

What are the components of a conceptual model?

The conceptual model comprised the following components: contextual factors, clinical interaction, attitudes and beliefs, and outcomes . Thirty-nine studies met inclusion criteria and were analyzed based on model components. Studies varied widely in quality, methodology, and sample size. Two provisional conclusions were identified: contrary to what is often reported in the literature, discussions about analgesics are most frequently characterized by patient-clinician agreement, and self-presentation during patient-clinician interactions plays an important role in communication about pain and opioids.

What are nonoverlapping circles?

The nonoverlapping portions of the circles denote attitudes and beliefs; these include the patient’s and clinician’s understanding of pain, treatment goals, beliefs about the cause of the patient’s pain, attitudes about opioids, and expectations for the visit.

How does pain affect communication?

Several studies in our review examined the relationship between pain severity and communication during visits [47,49,67–72]. Taken together, these studies suggest that the presence, severity, and chronicity of pain are associated with differences in the quality and content of patient-clinician communication. Two studies of patient affect [67,72] suggest that discussions about pain and pain severity may be associated with greater overall patient emotional arousal. Otherwise, apart from the unsurprising finding that patients who reported greater pain were more likely to discuss pain during clinic visits, direct comparisons and generalizations from these studies are difficult because they examine different patient populations with widely varying baseline characteristics and investigate different aspects of pain and communication.

Does Pt have a headache?

Pt states that she woke up with low grade abd pain and mild nausea, both of which have increased in severity throughout the day; pt has vomited 3x in past 5 hours (normal stomach contents) and has developed a low-grade headache. Pt has taken OTC medications (Dayquil, Advil) and attempted to rest with no relief.

Do agencies have documentation guidelines?

Most agencies have specific documentation guidelines. (I've never worked at one that hasnt) I'd check with your training officer.