Portal Hypertension: Introduction - Hopkins Medicine

14 hours ago Portal hypertension is a term used to describe elevated pressures in the portal venous system (a major vein that leads to the liver). Portal hypertension may be caused by intrinsic liver disease, obstruction, or structural changes that result in increased portal … >> Go To The Portal

Explore

Portal hypertension is a term used to describe elevated pressures in the portal venous system (a major vein that leads to the liver). Portal hypertension may be caused by intrinsic liver disease, obstruction, or structural changes that result in increased portal …

What is portal hypertension (portal hypertension)?

Portal hypertension is an increase in the pressure within the portal vein (the vein that carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver). The increase in pressure is caused by a blockage in the blood flow through the liver. Increased pressure in the portal vein causes large veins to develop across the esophagus and stomach to get around the blockage. The varices become …

How is clinically significant portal hypertension diagnosed?

Portal Hypertension Diagnosis. There are a number of ways to diagnose portal hypertension. For patients with end-stage liver disease who present with ascites and varices, the doctor may not need to perform any diagnostic tests and can confirm a diagnosis based on symptoms. Diagnostic procedures your doctor may order include: Imaging and blood tests

What are the suprahepatic causes of portal hypertension?

Portal hypertension is a clinical syndrome characterized by splenomegaly, ascites, gastrointestinal varices, and encephal-opathy and is defined by a hepatic vein pressure gradient (HVPG) exceeding 5 mm Hg.1 Portal hypertension is the major cause of severe complications and death in patients with cirrhosis.1 Portal hypertension also can develop in the

What is the first book on portal hypertension?

Jun 04, 2021 · Indeed, recently it was shown in a large prospective series of patients that severe portal hypertension induces an unstable course of disease after an acute decompensating event,129 at least partly due to bacterial infections,6 and secondary to variceal bleeding episodes in at least 20% of cases.130.

What are clinical findings in a patient with portal hypertension?

The main symptoms and complications of portal hypertension include: Gastrointestinal bleeding marked by black, tarry stools or blood in the stools, or vomiting of blood due to the spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage from varices. Ascites (an accumulation of fluid in the abdomen)

What are the clinical findings and etiology of portal hypertension?

Symptoms and signs of portal hypertension include: Gastrointestinal bleeding: You may notice blood in the stools, or you may vomit blood if any large vessels around your stomach that developed due to portal hypertension rupture. Ascites: When fluid accumulates in your abdomen, causing swelling.

What is the most common complication of portal hypertension?

Variceal hemorrhage is the most common complication associated with portal hypertension. Almost 90% of patients with cirrhosis develop varices, and approximately 30% of varices bleed. The estimated mortality rate for the first episode of variceal hemorrhage is 30-50%.

What is associated with portal hypertension?

Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension, and chronic viral hepatitis C is the most common cause of cirrhosis in the United States. Alcohol-induced liver disease and cholestatic liver diseases are other common causes of cirrhosis.

What are the 3 categories of portal hypertension?

With regard to the liver itself, causes of portal hypertension usually are classified as prehepatic, intrahepatic, and posthepatic.

What is the pathophysiology of portal hypertension?

Portal hypertension is characterized by a pathologic increase in portal venous pressure that leads to the formation of an extensive network of portosystemic collaterals that divert a large fraction of portal blood to the systemic circulation, bypassing the liver.

What is the most significant clinical consequence of portal hypertension?

The main symptoms and complications of portal hypertension include: Gastrointestinal bleeding: Black, tarry stools or blood in the stools; or vomiting of blood due to the spontaneous rupture and bleeding from varices. Ascites: An accumulation of fluid in the abdomen.

How do you manage portal hypertension?

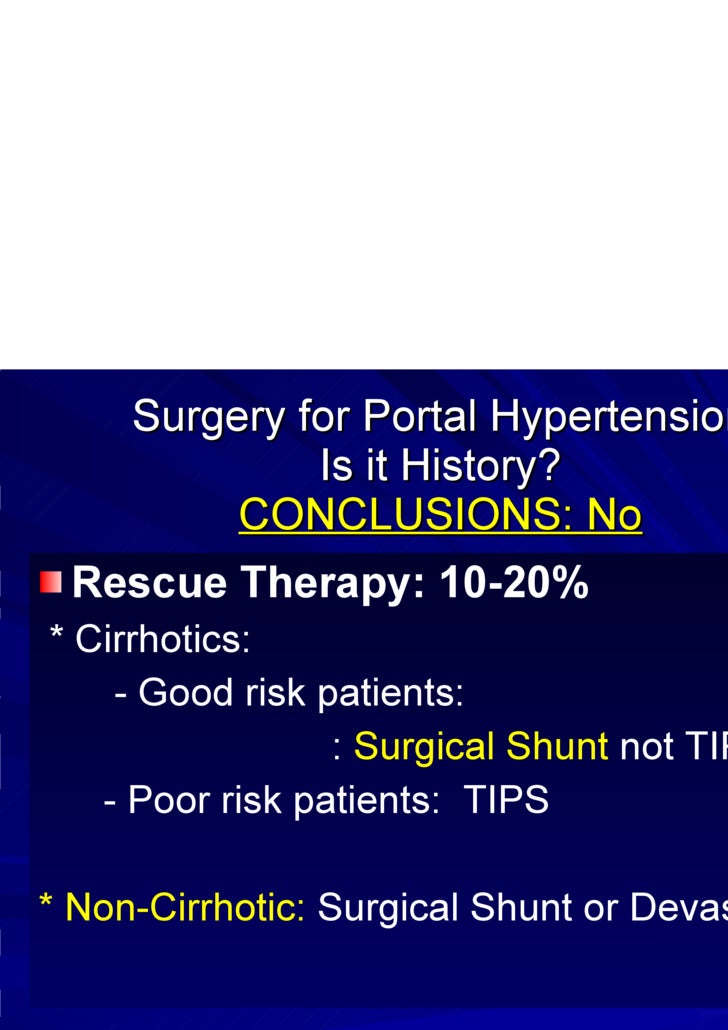

Pharmacologic therapy for portal hypertension includes the use of beta-blockers, most commonly propranolol and nadolol. Brazilian investigators have suggested that the use of some statins (eg, simvastatin) may lower portal pressure and potentially improve the liver function.

Can you feel portal hypertension?

Portal hypertension itself does not cause symptoms, but some of its consequences do. If a large amount of fluid accumulates in the abdomen, the abdomen swells (distends), sometimes noticeably and sometimes enough to make the abdomen greatly enlarged and taut. This distention can be uncomfortable or painful.

Can you live a normal life with portal hypertension?

It may take a combination of a healthy lifestyle, medications, and interventions. Follow-up ultrasounds will be necessary to monitor the health of your liver and the results of a TIPSS procedure. It will be up to you to avoid alcohol and live a healthier life if you have portal hypertension.

What stage of liver disease is portal hypertension?

Portal hypertension is defined as the pathological increase of portal venous pressure, mainly due to chronic end-stage liver disease, leading to augmented hepatic vascular resistance and congestion of the blood in the portal venous system.

How does hypertension affect the liver?

Portal hypertension may be due to increased blood pressure in the portal blood vessels, or resistance to blood flow through the liver. Portal hypertension can lead to the growth of new blood vessels (called collaterals) that connect blood flow from the intestine to the general circulation, bypassing the liver.

What is portal hypertension?

Portal hypertension is an increase in the pressure within the portal vein, which carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver. The most common cause is cirrhosis of the liver, but thrombosis (clotting) might also be the cause.

Why does blood pressure increase?

The increase in pressure is caused by a blockage in the blood flow through the liver. Increased pressure in the portal vein causes large veins ( varices) to develop across the esophagus and stomach to get around the blockage. The varices become fragile and can bleed easily.

What veins are used for TIPS?

During the TIPS procedure, a radiologist makes a tunnel through the liver with a needle, connecting the portal vein (the vein that carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver) to one of the hepatic veins (the 3 veins that carry blood from the liver). A metal stent is placed in this tunnel to keep the tunnel open.

How to treat encephalopathy?

This condition can be treated with medications, diet or by replacing the shunt.

Is TIPS a surgical procedure?

The TIPS procedure is not a surgical procedure. The radiologist performs the procedure within the vessels under X-ray guidance.

What is DSRS surgery?

The DSRS is a surgical procedure. During the surgery, the vein from the spleen (called the splenic vein) is detached from the portal vein and attached to the left kidney (renal) vein. This surgery selectively reduces the pressure in your varices and controls the bleeding.

Can liver disease cause portal hypertension?

But if you have liver disease that leads to cirrhosis, the chance of developing portal hypertension is high. The main symptoms and complications of portal hypertension include: Gastrointestinal bleeding: Black, tarry stools or blood in the stools; or vomiting of blood due to the spontaneous rupture and bleeding from varices.

What is the best way to diagnose portal hypertension?

Endosco pic Diagnosis. Endoscopy is another way to diagnose varices, which are large vessels associated with portal hypertension. An endoscopy can provide a definitive diagnosis of the varices and allow your doctor to treat and reduce the risk of bleeding or active bleeding. During a gastrointestinal endoscopy, your doctor can see ...

What is the purpose of a radiologist's pressure study?

An interventional radiologist may perform a pressure measurement study to evaluate the level of pressure in the hepatic (liver) vein. This can be done as an outpatient, where a radiologist will access one of your veins, usually via internal jugular vein.

How to tell if you have ascites?

Ascites is excess fluid in your abdominal cavity. Patients with chronic liver disease often develop ascites, though it may be caused by other factors. Symptoms of ascites include: 1 Early feeling of fullness 2 Increase in size of abdomen 3 Feeling out of breath (if the fluid begins pushing on your lungs)

What is a Doppler ultrasound?

A Doppler ultrasound uses sound waves to see how the blood flows through your portal vein. The ultrasound gives your doctor a picture of the blood vessel and its surrounding organs, as well as the speed and direction of the blood flow through the portal vein.

Can portal hypertension be diagnosed?

For patients with end-stage liver disease who present with ascites and varices, the doctor may not need to perform any diagnostic tests and can confirm a diagnosis based on symptoms.

Is portal hypertension a hepatic encephalopathy?

Hepatic encephalopathy is impairment in neuropsychiatric function associated with portal hypertension. Symptoms are usually mild, with subtle changes in behavior, changes in sleep pattern, mild confusion or slurred speech. However, it can progress to more serious symptoms, including severe lethargy and coma. Although we lack clear understanding of encephalopathy, there is an association with increase in ammonia concentration in the body. (However this does not correlate to regular blood test levels of ammonia).

What side of the body do you lie on?

You lie on your left side, referred to as the left lateral position. Your doctor inserts the endoscope (a thin, flexible, lighted tube with a camera) through your mouth and pharynx, into the esophagus. Your doctor can visualize the esophagus, stomach and duodenum with the endoscope.

What are the consequences of portal hypertension?

The most important clinical consequences of portal hypertension are related to the formation of portal-systemic collaterals; these include gastroesophageal varices, which are responsible for the main complication of portal hypertension, massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding (91).

What is the HVPG level for esophageal varices?

Cross-sectional and prospective studies have shown that esophageal varices do not bleed below a threshold HVPG level of 11 to 12 mm Hg (1,97,99). Importantly, it has also been demonstrated in prospective studies that variceal hemorrhage does not occur if the HVPG is reduced, either spontaneously or pharmacologically, to levels below 12 mm Hg (4,97,99) or more than 20% from baseline (104). The reduction in risk for bleeding occurs despite the continued demonstration of varices in the majority of patients. However, variceal size is significantly decreased when the HVPG is reduced below threshold values (4,99).

How much does variceal bleeding occur?

The incidence of variceal bleeding is about 4% per year in nonselected patients who have never bled at the time of diagnosis (100,101). The risk is much lower (between 1% and 2%) in patients without varices at the first examination; it increases to about 5% per year in those with small varices and to 15% per year in those with medium or large varices at diagnosis (102).

How early can you rebleed?

Early rebleeding is significantly associated with a risk for death within 6 weeks, which suggests that the prevention of early rebleeding should be a primary objective of the therapeutic approach to variceal bleeding. The incidence of early rebleeding ranges from 30% to 40% in the first 6 weeks. The risk peaks in the first 5 days, with 40% of all episodes of rebleeding occurring in this very early period, remains high during the first 2 weeks, and then declines slowly during the next 4 weeks. After 6 weeks, the risk for further bleeding becomes virtually equal to that before bleeding (115).

Is portal hypertension a complication of cirrhosis?

Portal hypertension is an almost unavoidable complication of cirrhosis. The prevalence of esophageal varices is very high; when cirrhosis is diagnosed, varices are present in about 40% of compensated patients and in 60% of those who present with ascites (95,96).

What is the most widely used indicator of risk for first variceal bleeding?

The estimated size of varices at endoscopy is the most widely used indicator of risk for first variceal bleeding. Patients with medium-sized to large varices are considered to be at considerable risk for bleeding, and they should receive therapy to prevent variceal bleeding (100,110). Other clinical and hemodynamic indicators are used only in clinical research.

How long does it take to die from variceal bleeding?

Because it may be difficult to assess the true cause of death (i.e., bleeding vs. liver failure or other adverse events), the general consensus is that any death occurring within 6 weeks after hospital admission for variceal bleeding should be considered a bleeding-related death. Six-week mortality after variceal bleeding is about 30%. Almost 60% of deaths are caused by uncontrolled bleeding, either during the initial episode or after early rebleeding. Like the risk for rebleeding, the risk for mortality peaks during the first days after bleeding, slowly declines thereafter, and after 6 weeks becomes constant and virtually equal to that before bleeding (115,116).