Nursing Care Plan for Abdominal Pain | NURSING.com

28 hours ago 9 rows · In the case of abdominal pain, a patient might report feeling: Abdominal pain; Decreased ... >> Go To The Portal

In the case of abdominal pain, a patient might report feeling: Abdominal pain Decreased appetite Nausea

Full Answer

Can a nurse write a care plan for abdominal pain?

This lesson will look at how a nurse can write a care plan for abdominal pain no matter the underlying diagnosis. Understand and explain the nursing interventions and rationales associated with an abdominal pain nursing care plan

How is acute abdominal pain evaluated in the emergency department?

Acute abdominal pain (AAP) is a common symptom in the emergency department (ED). Because abdominal pain can be caused by a wide spectrum of underlying pathology, evaluation of abdominal pain in the ED requires a comprehensive approach, based on patient history, physical examination, laboratory tests and imaging studies.

What factors predict the need for hospitalization for abdominal pain?

Our data from this small prospective clinical trial suggest that increasing abdominal pain intensity, presence of Murphy or McBurney signs, abnormal radiologic findings and elevated CRP are potential predictors of the need for hospitalization.

How do you assess abdominal pain?

Making an individualized assessment of abdominal pain begins by focusing on the available background information of the patient: health history, current health status, psychological state, and other relevant data. Subjective data is information or symptoms reported by the patient.

How do you assess a patient with abdominal pain?

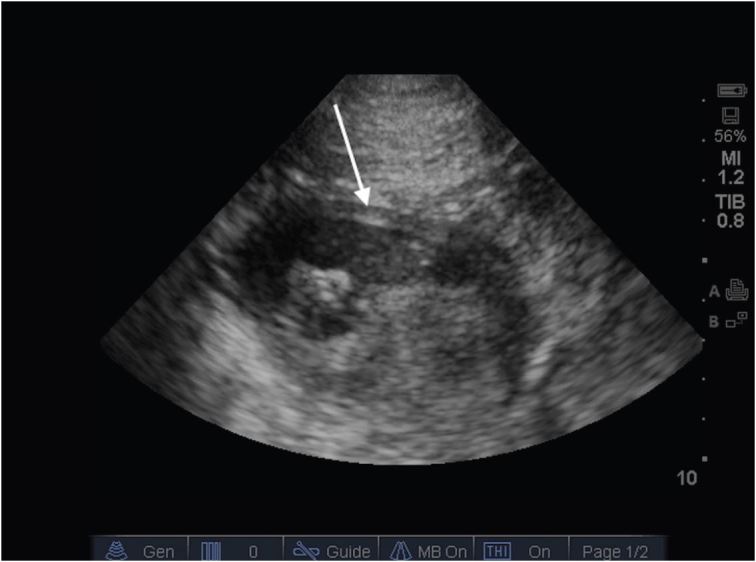

The American College of Radiology has recommended different imaging studies for assessing abdominal pain based on pain location. Ultrasonography is recommended to assess right upper quadrant pain, and computed tomography is recommended for right and left lower quadrant pain.

What should I ask a patient with abdominal pain?

5 Questions to Ask If You Have Stomach PainSeverity: Is the pain so severe that when it's present, you can't focus on or do other things?Vomiting: Are you also vomiting? ... Output: Okay, no one likes to talk about this, but I'm a doctor, so I have to ask. ... Other symptoms: Are you having difficulty breathing?More items...

What assessment findings might you find in a patient complaining of abdominal pain?

Abdominal assessment may reveal a mass in the right lower quadrant that is tender to palpation, or signs of peritoneal irritation such as rebound, involuntary guarding and abdominal wall muscle spasms. Any movement of the patient (e.g., bumping the stretcher) may elicit severe pain.

How do you assess for abdominal pain in nursing?

Nurses: Here's how to pinpoint source of abdominal painDo serial assessments. ... Get a rectal temperature. ... At triage, consider MIs. ... Check respiratory rates and blood pressure. ... Consider orthostatics. ... Expedite urinalysis. ... Be proactive to ensure fast test results. ... Ask children with abdominal pain to hop.More items...•

How do you document abdominal assessment?

Documentation of a basic, normal abdominal exam should look something along the lines of the following: Abdomen is soft, symmetric, and non-tender without distention. There are no visible lesions or scars. The aorta is midline without bruit or visible pulsation.

How do you do an abdominal assessment?

11:4514:25Abdominal Assessment -Clinical Skills- - YouTubeYouTubeStart of suggested clipEnd of suggested clipYou can try to feel for them using the belottment. Test with your fingers straight and stiff quicklyMoreYou can try to feel for them using the belottment. Test with your fingers straight and stiff quickly and briefly push onto the abdominal.

What are the 4 parts in order for abdominal assessment?

The abdominal examination consists of four basic components: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. It is important to begin with the general examination of the abdomen with the patient in a completely supine position.

Why do we assess for abdominal pain?

Article Sections. Acute abdominal pain can represent a spectrum of conditions from benign and self-limited disease to surgical emergencies. Evaluating abdominal pain requires an approach that relies on the likelihood of disease, patient history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies.

Why is abdominal assessment important?

If life-threatening intestinal pathology exists, most commonly obstruction, perforation, ischemia, or volvulus, a rapid and diagnostic abdominal examination will be the single most important factor to avoid mortality and to minimize morbidity.

How do you write a nursing diagnosis?

A nursing diagnosis has typically three components: (1) the problem and its definition, (2) the etiology, and (3) the defining characteristics or risk factors (for risk diagnosis). BUILDING BLOCKS OF A DIAGNOSTIC STATEMENT. Components of an NDx may include problem, etiology, risk factors, and defining characteristics.

What is the purpose of the abdominal review?

This review seeks to provide an understanding of the pathophysiological basis and an approach to assessing the cause of abdominal pain in adults by primary care practitioners . Key aspects of history and physical examination will be discussed with the view to enhance appropriate and accurate assessments, management and early referral to higher levels of care.

What is the most common abdominal pain?

Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome is the most common and often passed-over type of abdominal wall pain.11This condition typically presents with acute or chronic localised pain at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis that worsens with positional changes or increased abdominal muscle tension.12Abdominal wall pain should be suspected in patients with no symptoms or signs of visceral aetiology and a localised small tender spot. A positive Carnett test, in which tenderness stays the same or worsens when the patient tenses the abdominal muscles, suggests abdominal wall pain.8

What is the diagnostic challenge facing primary care physicians regarding patients with abdominal pain, considering the spectrum of symptoms, diagnoses and?

The diagnostic challenge facing primary care physicians regarding patients with abdominal pain, considering the spectrum of symptoms, diagnoses and management, present s a potential risk of delaying treatment for acutely ill patients.5

What percentage of patients with abdominal pain are admitted to the emergency department?

Abdominal pain is one of the most common complaints of patients admitted to emergency units, accounting for 5% – 10% of all presentations.1,2,3Evaluation of the emergency department patient with acute abdominal pain may be difficult as several factors can obscure the clinical findings resulting in incorrect diagnoses and subsequent adverse outcomes.4Primary care practitioners must therefore consider multiple diagnoses whilst giving priority to life-threatening conditions that require meticulous management to prevent morbidity and mortality. Skill in the assessment of a patient presenting with abdominal pain is essential for all primary care doctors.

What stimuli stimulate the pain receptors in the abdomen?

Pain receptors in the abdomen are stimulated by mechanical and chemical stimuli. Stretch is the primary mechanical stimulus whilst visceral mucosal receptors respond to chemical stimuli.7The precise events responsible for the perception of abdominal pain is not well understood but depend on the type of stimulus and the interpretation of visceral nociceptive inputs in the central nervous system.

Why is visceral pain ill defined?

Localisation of visceral pain is ill-defined because of the type and density of visceral afferent nerves. The pain is usually perceived in the midline because most abdominal organs are innervated by afferent nerves from both sides of the spinal cord.7However, pain that is lateralised may arise from the ipsilateral kidney, ureter or ovary.7A summary of the mechanisms of abdominal pain is presented in Table 2.

Where does abdominal pain come from?

Abdominal pain may originate from within the peritoneal cavity, the retro peritoneum, the pelvis, the abdominal wall or even from outside the abdomen. The physiological basis for intra-abdominal pain is listed in Table 1.

How to determine if you have peritonitis?

Determining the presence or absence of peritonitis is a primary objective of the abdominal examination; unfortunately, the methods for detecting it are often inaccurate. Traditional rebound testing is performed by gentle depression of the abdominal wall for approximately 15–30 seconds with sudden release. The patient is asked whether the pain was greater with downward pressure or with release. Despite limitations, the test was one of the most useful in a meta-analysis of articles investigating the diagnosis of appendicitis in children.29Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomenrecommends against this test because it is unnecessarily painful. The authors suggest gentle percussion as more accurate and humane.28When subject to study, traditional rebound testing has a sensitivity for the presence of peritonitis near 80%, yet its specificity is only 40%–50% and it is entirely nondiscriminatory in the identification of cholecystitis.27,33,34The use of indirect tests such as the “cough test,” where one looks for signs of pain such as flinching, grimacing, or moving the hands to the abdomen upon coughing has a similar sensitivity but with a specificity of 79%.35In children, indirect tests would include the “heel drop jarring” test (child rises on toes and drops weight on heels) or asking the child to jump up and down while looking for signs of abdominal pain.29,36

What is abdominal ED?

The ED abdominal exam is directed primarily to the localization of tenderness, the identification of peritonitis, and the detection of certain enlargements such as the abdominal aorta. Various strategies have been advocated to improve the palpation phase of the examination, including progression from nonpainful areas to the location of pain. It may be useful to palpate the abdomen of anxious or less cooperative children with the stethoscope to define areas of tenderness.29Meyerowitz30advocates following up the initial examination with a secondary palpation with a stethoscope while telling the patient one is listening in order to uncover exaggerated symptoms. It is preferable to have the patient flex the knees and hips to allow for relaxation of the abdominal musculature (see below discussion of guarding).

What is acute onset pain?

Acute-onset pain, especially if severe, should prompt immediate concern about a potential intra-abdominal catastrophe. The foremost consideration would be a vascular emergency such as a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) or aortic dissection. Other considerations for pain of acute onset include a perforated ulcer, volvulus, mesenteric ischemia, and torsion; however, these conditions may also occur without an acute onset. For example, only 47% of elderly patients with a proven perforated ulcer report the acute onset of pain.8Likewise, volvulus, particularly of the sigmoid colon, can present with a gradual onset of pain.9Serious vascular issues such as mesenteric ischemia may present with a gradual onset of pain. Conversely, one would expect a gradual onset in the setting of an infectious or inflammatory process. Pain that awakens the patient from sleep should be considered serious until proven otherwise.10The time of onset establishes the duration of the pain and allows the physician to interpret the current findings in relation to the expected temporal progression of the various causes of abdominal pain.

What is somatic pain?

Somatic pain is transmitted via the spinal nerves from the parietal peritoneum or mesodermal structures of the abdominal wall. Noxious stimuli to the parietal peritoneum may be inflammatory or chemical in nature (eg, blood, infected peritoneal fluid, and gastric contents).5,7

How long does gallbladder pain last?

Although labeled “colic,” gallbladder pain is generally not paroxysmal, and it almost never lasts less than 1 hour, with an average of 5–16 hours’ duration, and ranging up to 24 hours.13Small bowel obstruction typically progresses from an intermittent (“colicky”) pain to more constant pain when distention occurs.

What organs cause pain in the suprapubic region?

Hindgut structures such as the bladder, and distal two-thirds of the colon, as well as pelvic genitourinary organs usually cause pain in the suprapubic region. Pain is usually reported in the back for retroperitoneal structures such as the aorta and kidneys.5,6. Character .

What should a clinician try to obtain?

The clinician should try to obtain as complete a history as possible as this is generally the cornerstone of an accurate diagnosis. The history should include a complete description of the patient’s pain and associated symptoms. Medical, surgical, and social history should also be sought as this may provide important information.

How to stop abdominal pain from stress?

Manage your stress. Stress may cause abdominal pain. Your healthcare provider may recommend relaxation techniques and deep breathing exercises to help decrease your stress. Your healthcare provider may recommend you talk to someone about your stress or anxiety, such as a counselor or a trusted friend. Get plenty of sleep and exercise regularly.

How to help with abdominal pain?

Keep a diary of your abdominal pain. A diary may help your healthcare provider learn what is causing your abdominal pain. Include when the pain happens, how long it lasts, and what the pain feels like. Write down any other symptoms you have with abdominal pain. Also write down what you eat, and what symptoms you have after you eat.

What does it mean when you have a fever?

You have new chest pain or shortness of breath. You have pulsing pain in your upper abdomen or lower back that suddenly becomes constant. Your pain is in the right lower abdominal area and worsens with movement. You have a fever over 100.4°F (38°C) or shaking chills.

How long does it take for a swollen bowel to go away?

You are vomiting and cannot keep food or liquids down. Your pain does not improve or gets worse over the next 8 to 12 hours. You see blood in your vomit or bowel movements, or they look black and tarry. Your skin or the whites of your eyes turn yellow.

Why does my abdomen hurt?

Your pain may be caused by a condition such as constipation, food sensitivity or poisoning, infection, or a blockage. Abdominal pain can also be from a hernia, appendicitis, or an ulcer. Liver, gallbladder, or kidney conditions can also cause abdominal pain.

What foods can cause gas?

Do not eat foods that cause gas if you have bloating. Examples include broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower. Do not drink soda or carbonated drinks. These may also cause gas.

Can alcohol cause abdominal pain?

Limit or do not drink alcohol. Alcohol can make your abdominal pain worse. Ask your healthcare provider if it is safe for you to drink alcohol. Also ask how much is safe for you to drink.

Why is AAP a problem in the ED?

AAP is a common problem in the ED, requires use of hospital resources and significantly contributes to health care cost [5], and patient evaluation can be challenging, because multiple diagnoses need to be considered in a limited time frame, and available information can be inconclusive.

What is AAP in ED?

Acute abdominal pain (AAP) is a common symptom in the emergency department (ED). Because abdominal pain can be caused by a wide spectrum of underlying pathology, evaluation of abdominal pain in the ED requires a comprehensive approach, based on patient history, physical examination, laboratory tests and imaging studies.

What does it mean when your abdomen is rigid?

If the abdomen is rigid, it may suggest blood, digestive juices, or bowel material may be present in the peritoneal cavity. Note any masses that could suggest tumors, obstructed bowel or aneurysms. Monitor the patient’s vital signs and watch for signs of shock.

What is the pain in the parietal wall called?

Parietal pain, also known as somatic pain , is caused by irritation to the parietal peritoneal wall. This type of pain is commonly described as “sharp” and “pinpoint” pain. When asked to localize their pain, patients will point to a specific spot. For example, patients with an inflamed appendix may point to a spot in the middle of the right lower quadrant known as McBurney’s point. These patients may feel better with their knees drawn up, which relaxes the peritoneum.

Is abdominal pain life threatening?

Abdominal pain can be a difficult complaint to assess. Many causes of abdominal pain aren’t life-threatening, but some are. It may be difficult for you as an EMS provider to identify the exact cause of the pain, but you should be able to identify potential life-threatening causes and transport appropriately.

What is the Meckel's diverticulum?

Meckel’s diverticulum is a true diverticulum comprised of all 3 layers of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract including mucosa, submucosa, and adventitia.[2] Meckel’s diverticulum usually consists of heterotopic tissue, most commonly gastric mucosa, due to the pluripotential cell line of the omphalomesenteric duct.

What is the diverticulum?

The diverticulum can also serve as a lead for point for an ileocolic or ileoileal intussusception as well as a turning point for a volvulus. If symptomatic, patients typically complain of crampy, right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

What tissue is found on a Meckel's diverticulum?

Other heterotopic tissue found on pathological specimens of Meckel's diverticulum may include pancreatic, jejunal, duodenal, and less commonly, colonic, rectal, or endometrial. Epidemiologically, Meckel’s diverticulum tends to follow the rule of 2s:[2] Occurs in 2% of the population.

Can diverticulum be removed after laparotomy?

In many cases, the diverticulum is found incidentally on laparotomy or laparoscopy, and it becomes the surgeon’s decision on whether or not to remove the diverticulum to prevent future complications. The lifetime risk of complications is 4.2%, and the risk decreases with age.[1] Therefore, the decision for diverticulectomy is favored in asymptomatic patients who are young and have a long diverticulum (typically greater than 2 cm) with a narrow neck and fibrous banding, or if it appears to be comprised of gastric mucosa and is inflamed or thickened. However, in a symptomatic patient, medical management is limited to supportive care including possible antibiotic administration and surgical resection is required for definitive treatment. [1]

What tests are performed for CBC?

Initial tests performed including blood testing consisting of a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), lipase, and liver function test (LFT), as well as a urinalysis. Lab work was remarkable for no acute abnormalities except for a mild leukocytosis of 12.4.

What does CV mean in medical terms?

Cardiovascular (CV): Regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, rubs, gallops

How many times as likely to be symptomatic in young boys as compared to young girls?

Two times as likely to be symptomatic in young boys as compared to young girls