Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: why …

21 hours ago Patient-Centered Care / organization & administration* Schools, Dental / organization & administration United States >> Go To The Portal

As discussed in the IOM’s Crossing the Quality Chasm

Crossing the Quality Chasm

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century is a report on health care quality in the United States published by the Institute of Medicine on March 1, 2001. A follow-up to the frequently cited 1999 IOM patient safety report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health S…

Full Answer

What is patient centered care and how is it better?

- treating you with dignity, respect and compassion

- communicating and coordinating your care between appointments and different services over time, such as when making a referral from your GP to a specialist

- or sharing your care between a community health service and a hospital

- tailoring the care to suit your needs and what you want to achieve

How to provide excellent patient centered care?

- The patient care environment should be peaceful and as stress free as possible. ...

- Patient safety is key. ...

- Patient care should be transparent. ...

- All caregivers should focus on what is best for the patient at all times.

- The patient should be the source of control for their care. ...

What are the principles of patient centered care?

- The health care system’s mission, vision, values, leadership, and quality-improvement drivers are aligned to patient-centered goals.

- Care is collaborative, coordinated, and accessible. ...

- Care focuses on physical comfort as well as emotional well-being.

Why is patient centred care so important?

Understanding the Importance of Patient-Centered Care

- The Eight Principles of Patient-centered Care

- Respecting Patient’s Values, needs, and Preferences. ...

- Coordination and Integration of Care. ...

- Physical Comfort. ...

- Emotional Support and Eliminating Fear and Anxiety. ...

- Family and Friends Involvement. ...

- Continuity and Transition. ...

- Asking the Right Questions. ...

What are patient-centered measures?

What are the dimensions of patient centeredness?

How do family and friends help with stroke patients?

What are some examples of patient-reported measures that assess information provision in relation to health care?

What is the gold standard for assessing cancer pain and fatigue?

How accurate is the psychosocial well being of cancer patients?

Why is patient centered care important?

See more

About this website

How does the IOM define patient-centered care?

The IOM (Institute of Medicine) defines patient-centered care as: “Providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”[1]

What is a patient-centered care report?

The PCMH improves the delivery of primary care by making primary care comprehensive, patient-centered, coordinated, accessible, and committed to quality and patient safety (Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative, n.d.). These functions help understand the health, economic, and cultural needs of specific patients.

What are the 5 key elements of patient-centered care?

Research by the Picker Institute has delineated 8 dimensions of patient-centered care, including: 1) respect for the patient's values, preferences, and expressed needs; 2) information and education; 3) access to care; 4) emotional support to relieve fear and anxiety; 5) involvement of family and friends; 6) continuity ...

What are the 4 C's of patient-centered care?

The four primary care (PC) core functions (the '4Cs', ie, first contact, comprehensiveness, coordination and continuity) are essential for good quality primary healthcare and their achievement leads to lower costs, less inequality and better population health.

How is patient-centered care measured?

Patient-reported measures are arguably the best way to measure patient-centeredness. For instance, patients are best positioned to determine whether care aligns with patient values, preferences, and needs and the Measure of Patient Preferences is an example of a patient-reported measure that does so.

What are examples of patient-centered care?

Patient-centered care examplesLetting the patient choose who can visit them.Allowing the patient to pick their own visiting hours.Inviting the patient's family members to participate in decision-making.Providing accommodations for visitors, like food and blankets.

What are the 7 core values of a person-Centred approach?

In health and social care, person-centred values include individuality, rights, privacy, choice, independence, dignity, respect and partnership.

What are the eight 8 core values of a client Centred approach?

The eight values in person-centred healthcare are individuality, rights, privacy, choice, independence, dignity, respect, and partnership.

Which 3 statements are characteristics of patient-centered care?

Defined by the Institute of Medicine as the act of "providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions," patient-centered care prizes transparency, compassion, and empowerment.

What are the 4 P's in nursing?

Attention will be focused on the four P's: pain, peripheral IV, potty, and positioning. Rounds will also include an introduction of the nurse or PCT to the patient, as well as an environmental assessment.

What is patient-centered care and why is it important?

Patient-centered care (PCC) has the potential to make care more tailored to the needs of patients with multi-morbidity. PCC can be defined as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” [9].

What are the 4 C in nursing?

The four Cs of communication in nursing include; Clear, Concise, Correct and Complete. These are very important aspects in nursing practice.

Quality Measurement and Quality Improvement | CMS

Quality Measurement and Quality Improvement What is quality improvement? Quality is defined by the National Academy of Medicine as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.. Quality improvement is the framework used to systematically improve care.

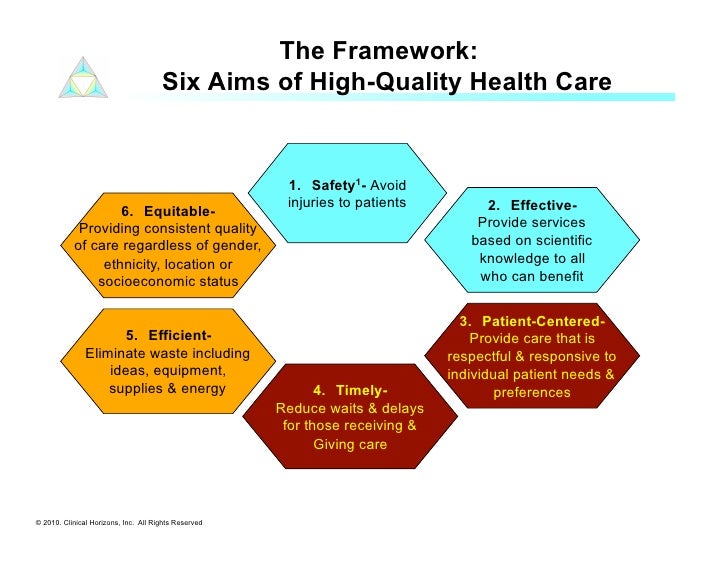

Table 2, [IOM’s Six Aims for Improving Health Care Quality ...

Aim Description; 1. Safe care: Avoiding injuries to patients: 2. Effective care: Providing care based on scientific knowledge: 3. Patient-centered care: Providing respectful and responsive care that ensures that patient values guide clinical decisions

Measuring Person-centered Care: A Critical Comparative Review of ...

Abstract. Purpose of the study: To present a critical comparative review of published tools measuring the person-centeredness of care for older people and people with dementia.Design and Methods: Included tools were identified by searches of PubMed, Cinahl, the Bradford Dementia Group database, and authors’ files. The terms “Person-centered,” “Patient-centered” and “individualized ...

Measuring Care Management Value: 5 Tools to Show Impact

When care management programs fail, it’s rarely because they’re ineffective. Most likely, it’s because health systems don’t have an accurate way to measure care management’s success and, therefore, don’t fully understand (or communicate) its impact on outcomes improvement or cost savings.. For care management programs to be successful and demonstrate their value around critical ...

How would patient centered care be paid?

In the U.S., patient-centered care practices could be paid a fixed monthly fee for a package of services such as e-mail visits, reminders, access to electronic medical records, and demonstrating easy access to care when needed by the patient. These payments would offset the additional personnel, physician time, information technology, and office system costs that would be required to deliver these services.

What are the attributes of patient centered care?

Seven attributes of patient-centered primary care are proposed here to improve this dimension of care: access to care, patient engagement in care, information systems, care coordination, integrated and comprehensive team care, patient-centered care surveys, and publicly available information . The Commonwealth Fund 2003 National Survey of Physicians and Quality of Care finds that one fourth of primary care physicians currently incorporate these various patient-centered attributes in their practices. To bring about marked improvement will require a new system of primary care payment that blends monthly patient panel fees with traditional fee-for-service payment, and new incentives for patient-centered care performance. A major effort to test this concept, develop a business case, provide technical assistance and training, and diffuse best practices is needed to transform American health care.

What is the difference between patient centered and quality care?

Berwick5has popularized the slogan adopted by the Salzburg group, “Nothing about me without me.” Quality is often defined as providing the right care in the right way at the right time, but a patient-centered vision would define quality as providing the care that the patient needs in the manner the patient desires at the time the patient desires. Because both patients and physicians desire good health outcomes, sometimes these 2 definitions are identical. Economists have talked about the physician as patient's agent—providing the care the patient would want if the patient had the information that the physician has. But increasingly, patients wish for direct access to that information, the ability to be active partners in their care, and the opportunity to share in treatment decisions.6,7

What is patient engagement?

Patient engagement in care: option for patients to be informed and engaged partners in their care, including a recasting of clinician roles as advisers, with patients or designated surrogates for incapacitated patients serving as the locus of decision making (when desired by patients); information for patients on condition/treatment options/treatment plan; clear delineation of roles and responsibilities for patients, caretakers, and clinicians; patient reminders/alerts for routine preventive care or when special follow-up is necessary (e.g., abnormal test results, or changes needed in dosage of a medication); patient access to their medical records and their ability to add or clarify information in the record; assistance with self-care; assistance with behavior change; patient education; and anticipatory guidance and counseling for parents on child health and development issues.

How to support the development of medical homes?

To support the development of medical homes within primary care practices, there would need to be new incentives for primary care physicians. A new system of payment for primary care could include both a medical home monthly fee to encourage better physician-patient communication and coordination of care, combined with the current fee-for-service payment system. The medical home fee component would need to be sufficient to cover the cost of nonreimbursable services such as information technology and other practice systems to ensure patient-centered care, such as patient surveys and patient reminder systems. A model for this could be the blended per-patient fee and fee-for-service system in use in Denmark.29In the U.S., Newhouse has advocated a blended payment system both as a way of adjusting for the greater health care needs of sicker enrollees and as a way of balancing incentives for overuse and underuse.35Medicare is currently considering pay for performance for physician services and could be a leader by paying a monthly panel fee as well as rewards for performance on patient-reported experiences with care. Demonstrations to test the concept would be an important first step.

How many primary care physicians make same day appointments?

Three fourths of primary care physicians now make same-day appointments available. Seventy percent of primary care physicians receive timely feedback from specialty referrals. The great majority support making medical records available to patients and support team-based care. About half have patient reminder systems (although only one fifth are automated systems). Two in 5 primary care physicians can create disease registries of patients with ease.8

Why is it important to provide solutions to primary care physicians?

Primary care physicians are feeling under siege, overworked, and underpaid.32–34So it is important to provide solutions that are realistic and do not create a new layer of problems. First, financial issues must be addressed head-on, and physicians must be given easy access to resources and tools that they can implement easily in their practice. The UK had the advantage of setting new expectations for primary care physicians at the same time it increased resources to finance health care—through a tax increase enacted specifically to improve access in the National Health Service. In the U.S., it may be necessary to achieve offsetting savings, either in specialty care or in reduced use of hospital and emergency room care to finance improved primary care.

What is patient centered communication?

patient-centered communication, which involves the patient, family, and friends; explains treatment options; and includes patients in treatment decisions to reflect patients' values, preferences, and needs;

What is patient centeredness?

The concept of patient-centeredness as an important attribute of high-quality health care gained national prominence with the IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century ( IOM, 2001 ). The IOM defines patient-centeredness as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” ( IOM, 2001, p. 40). 2 Over time, other organizations and individuals have elaborated on the attributes of patient-centered care ( Bechtel and Ness, 2010; Berwick, 2009; Epstein et al., 2010; Picker Institute, 2013 ). In the cancer setting, some of the attributes of patient-centered care highlighted at an IOM National Cancer Policy Forum workshop included ( IOM, 2011a)

What is the cause of communication problems in cancer patients?

A lack of understandable and easily available information on prognosis, treatment options, likelihood of treatment responses, palliative care, psychosocial support, and the costs of cancer care contribute to communication problems, which are exacerbated in patients with advanced cancer.1.

How does fragmentation affect cancer care?

Fragmentation of the cancer care delivery system also contributes to communication problems between patients and their care teams. Patients with cancer may need to coordinate care among multiple clinicians on their cancer care team and other care teams. Jessie Gruman, a four-time cancer survivor, pointed out that in 1 year, eight physicians cared for her, and yet only once did two of those physicians communicate directly with each other; she was primarily responsible for sharing her medical information among the different clinicians ( Gruman, 2013 ). It can be especially difficult for care team members to share information and communicate effectively with patients if the care team members' electronic health records (EHRs) are not interoperable (see Chapter 7 on additional information technology challenges). With system problems such as these, it can be unclear to patients and care teams who is responsible for each aspect of care and who needs to be contacted to address a treatment complication ( IOM, 2011a ). New models of care and reimbursement, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) or oncology patient-centered medical homes, may address some of these system challenges (see Chapter 8 ).

How can cancer information be used to improve patient care?

The availability of easily understood, accurate information on cancer prognosis, treatment benefits and harms, palliative care, psychosocial support, and likelihood of treatment response can improve patient-centered communication and shared decision making. A number of trusted organizations have developed print, electronic, and social resources to inform patients and their families about cancer, such as the NCI, the American Cancer Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Mayo Clinic, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, American Society of Clinical Oncology, LIVE STRONG, and the Susan G. Komen Foundation (see Table 3-2 for examples of patient resources). 5 However, there are some serious limitations with the type of information included in the available resources on cancer. In addition, there are a number of other websites that may contain inaccurate or outdated information. Thus, finding accurate, useful cancer information online can be a major challenge for patients and their families ( Chan et al., 2012; IOM, 2011a; Irwin et al., 2011; Lawrentschuk et al., 2012; Quinn et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2013 ).

How does communication help in cancer care?

One of the important functions of communication in cancer care is ensuring that patients make decisions that are consistent with their needs, preferences, and values. Clinicians have an important role in improving patient-centered communication and shared decision making by listening actively, assessing a patient's understanding of treatment options, validating a patient's participation in the decision-making process, and communicating empathy both verbally and nonverbally ( Epstein and Street, 2007 ). In addition, decision making can be improved through use of decision aids that facilitate patient understanding of treatment options and enable patients to take a more active role in decision making. A decision aid is a “tool that provides patients with evidence-based, objective information on all treatment options for a given condition. Decision aids present the risks and benefits of all options and help patients understand how likely it is that those benefits or harms will affect them” ( MedPAC, 2010, p. 195). Decision aids can include written material, Web-based tools, videos, and multimedia programs ( MedPAC, 2010 ). Some decision aids are designed for patient use and others are designed for clinicians to use with patients.

What are the factors that affect cancer care?

A number of factors related to cancer care necessitate a patient-centered approach to communication: (1) cancer care is extremely complex and patients' treatment choices have serious implications for their health outcomes and quality of life; (2) the evidence supporting many decisions in cancer care is limited or incomplete; and (3) trade-offs in the risks and benefits of cancer treatment choices may be weighed differently by individual patients , and clinicians need to elicit patient needs, values, and preferences in these circumstances. Each of these factors is discussed below.

How to track progress in providing equitable, patient-centered care?

Tracking our progress in providing equitable, patient-centered care requires a monitoring system that can give feedback that helps us evaluate how well we are doing. In the IOM report Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports [7], an updated framework is provided for measuring health care quality and disparities (see Figure 1) that continued the trend of highlighting the importance of equitable, patient-centered, high-quality care.

What are the principles of patient centered care?

To clarify, the authors of this paper suggest that the principles of patient-centered care include respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs; coordination and integration of care; and providing emotional support alongside the alleviation of fear and anxiety associated with clinical care. Similar to the NCQA report, the authors of this paper agree that patient-centered care initiatives are a parallel and possibly underlying dimension of health literacy, language access, and cultural competence efforts in that patient-centered health initiatives are associated with beneficial health outcomes, including improved patient experience, safety, and clinical effectiveness.

What is the IHI measure?

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) could add an integrated measure of health literacy, language access, and cultural competence to its Pursuing Equity in Health Care Systems initiative [21]. This addition to IHI’s planned quality improvement activities could foster an evidence base that better documents overall progress to achieve health equity. IHI, a leading national organization supporting health care quality improvement, launched a two-year Pursuing Equity initiative with eight health care systems across the nation in 2017. The participating health care systems apply practical improvement methods and tools, spread ideas in peer-to-peer learning, and disseminate results and lessons to support an ongoing national dialogue to advance health equity. Specifically, an integrated measure could be tested as part of IHI’s Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations, which features five strategies [22]:

What is the importance of cultural competence in health care?

An integrated measure of health literacy, language access, and cultural competence could reduce health disparities, could highlight patient engagement, would contribute to improvement in patient care practices, and would not duplicate existing improvement activities.

How many measures of health literacy are there?

Yet after a review of relevant self-assessment efforts within US health care organizations, NCQA found that only four measures evaluated health literacy, language access, or cultural competence services. Three of these four measures did not focus on patient care and instead evaluated some characteristics of extant health plans, such as the diversity of plan members and the availability of language assistance within a health plan.

What is NCQA?

NCQA concluded that implementing more health literacy, language access, and cultural competence initiatives within the health care delivery system could contribute to improved health care in the United States—and that ensuring quality improvements might occur if these activities were assessed systematically.

How can we reduce health disparities?

Reducing disparities requires attention to the essential components of equitable, patient-centered, high-quality care—that is, to culturally and linguistically appropriate care as well as attention to health literacy. Low health literacy disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities and contributes to health disparities. It should be noted, however, that challenges of health literacy affect all segments of the population. According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), “The primary responsibility for improving health literacy lies with public health professionals and the health care and public health systems. It is imperative to ensure that health information and services can be understood and used by all Americans. We must engage in skill building with health care consumers and health professionals” [5]. A 2009 IOM workshop reported that “Integrating quality improvement, health literacy, and disparities reduction emphasizes the intersection of the patient-centered and equitable aims” [6].

Who is the sponsor of the IOM report?

NCCS is a sponsor of the IOM report, along with other patient advocacy organizations, professional societies, and government agencies. As a leader in advocating for quality cancer care from the moment of diagnosis, through treatment and beyond, NCCS commends the IOM for its recognition of the challenges facing the cancer care delivery system and supports the findings and recommendations.

Is cancer care patient centered?

Today, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its report, “Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis.” According to the IOM, the American cancer care system often is not patient-centered, does not provide well-coordinated care, and does not encourage evidence-based treatment decisions.

What is patient centered care?

Patient-centered: Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

Why are IOM domains important?

Frameworks like the IOM domains also make it easier for consumers to grasp the meaning and relevance of quality measures. Studies have shown that providing consumers with a framework for understanding quality helps them value a broader range of quality indicators. For example, when consumers are given a brief, understandable explanation of safe, ...

What are the six aims of the health care system?

[1] Safe: Avoiding harm to patients from the care that is intended to help them. Effective: Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit ...

What is the definition of equitable care?

Equitable: Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

What are patient-centered measures?

Patient-reported measures developed to assess the quality of patient-centered care include measures of satisfaction with care and measures of experiences of care.5,6Patient-reported measures are essential to quality improvement efforts as they provide the patient’s perspective in relation to areas of health care that are of high quality and aspects of care where improvements are needed.7Patient-reported measures are arguably the best way to assess constructs that relate to patient-centeredness given that patient-centered care is responsive to the patient and is guided by patient preferences.1Patient-reported measures are also able to collect information that can only be obtained from patients themselves such as whether the patient received adequate pain relief.8

What are the dimensions of patient centeredness?

The IOM endorsed six patient-centeredness dimensions that stipulated that care must be: respectful to patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs; coordinated and integrated; provide information, communication, and education; ensure physical comfort; provide emotional support; and involve family and friends. Patient-reported measures examine the patient’s perspective and are essential to the accurate assessment of patient-centered care. This article’s objectives are to: 1) use the six IOM-endorsed patient-centeredness dimensions as a framework to outline why patient-reported measures are crucial to the reliable measurement of patient-centered care; and 2) to identify existing patient-reported measures that assess each patient-centered care dimension.

How do family and friends help with stroke patients?

The IOM recommended that family and friends are involved in patient care and decision-making according to patient preferences and that care is responsive to the needs of family and friends.1Family and friends can improve patient-provider rapport, facilitate information exchange , encourage decision-making involvement, and increase patient satisfaction.42However, families and friends of stroke patients have reported feeling inadequately informed about and involved in patient care.43A review found that major issues faced by cancer caregivers included managing their own and patient’s psychological concerns, medical symptoms, side effects, and daily activities.44Family members of cancer patients have been found to be more likely to have unmet needs about information in relation to supportive care than for medical information.45

What are some examples of patient-reported measures that assess information provision in relation to health care?

Examples of patient-reported measures that assess information provision in relation to health care include the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire, developed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients,23and the EORTC QLQ-INFO25 a measure for cancer patients.24

What is the gold standard for assessing cancer pain and fatigue?

Patient-reported measures are recognized as the gold standard for assessing cancer pain and fatigue.33Only patients themselves can report the severity of fatigue, pain or physical symptoms, and whether medications provide adequate pain relief. This highlights the importance of using patient-reported measures to determine whether health care appropriately attends to patient comfort. Patient-reported measures that assess physical comfort include the Pain Care Quality Survey,34the Brief Pain Inventory used for clinical pain assessment across cultures,35and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Pain Interference measure.36

How accurate is the psychosocial well being of cancer patients?

Clinician accuracy of patient psychosocial well-being can be poor, as demonstrated by only 17% of cancer patients classified as clinically anxious and 6% as clinically depressed perceived as such by oncologists.39Using patient-reported measures to assess the level of emotional support provided can inform quality improvement efforts by determining if health care services adequately address patients’ emotional needs and reduce psychological distress. Widely used patient-reported measures for assessing the emotional well-being of patients include the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale40and Beck Depression Inventory.41

Why is patient centered care important?

Accurate measurement of the quality of patient-centered care is essential to informing quality improvement efforts. Using patient-reported measures to measure patient-centered care from patients’ perspectives is critical to identifying and prioritizing areas of health care where improvements are needed. Patients are well positioned to provide reliable and valid information about the delivery of patient-centered care. For instance, only patients are able to accurately determine whether care was respectful to patients’ values, preferences, and needs. Regularly using patient-reported measures to accurately assess the quality of patient-centered care could assist with promptly identifying areas of care where improvements are required and consequently may facilitate advancements to the delivery of patient-centered care.

Popular Posts:

- 1. thomas chittenden health center patient portal

- 2. hca portal patient

- 3. https://www.aboutskinderm.com patient portal

- 4. whs.org patient portal

- 5. spectrum cottonwood patient portal

- 6. adena.org patient portal

- 7. ortho sc patient portal

- 8. patient portal poland medical center

- 9. mychart patient portal allegheny health network

- 10. dr. crop utah patient portal