What is a patient portal? | HealthIT.gov

10 hours ago Dec 02, 2021 · Integrated patient portal software functionality usually comes as a part of an EMR system, an EHR system or practice management software. But at their most basic, they’re simply web-based tools. You can use patient portals to retrieve lab results, ask a question or update patient profiles and insurance providers. Some patient portals also ... >> Go To The Portal

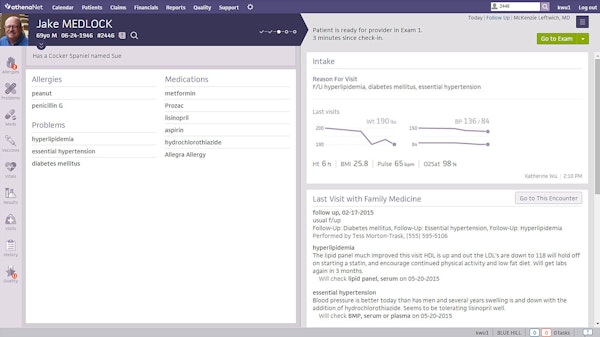

What is a patient portal?

Dec 02, 2021 · Integrated patient portal software functionality usually comes as a part of an EMR system, an EHR system or practice management software. But at their most basic, they’re simply web-based tools. You can use patient portals to retrieve lab results, ask a question or update patient profiles and insurance providers. Some patient portals also ...

Does patient condition influence portal use among cancer patients?

Sep 19, 2017 · Patient portal benefits include patients’ ability to access their clinical summaries online. Providers can also send lab results to patients via secure messaging accompanied by a brief message explaining the results (for example, “Your results are normal”) and any needed follow‐up instructions (for example, “Come back in 3 months for a recheck”).

Do patient requests for nonclinical information and functions affect portal development?

Apr 11, 2016 · April 11, 2016 - In order to accrue financial benefits from implementing a patient portal, healthcare organizations must understand how their customers want to use the technology and why it’s important to keep the tool patient-centered. As risk-based payment models such as accountable care organizations gain industry popularity, providers need to implement patient …

How often do patients have access to the portal?

Apr 11, 2019 · Patient portals can provide secure, online access to personal health information [ 1] such as medication lists, laboratory results, immunizations, allergies, and discharge information [ 2 ]. They can also enable patient-provider communication using secure messaging, appointments and payment management, and prescription refill requests [ 2, 3 ].

What is a patient portal used for?

What does patient portal contain?

What are the different types of patient portals?

What are the five main features of the new healthcare portal?

- Easy to follow user interface. ...

- Messaging and communication. ...

- Registration. ...

- Scheduling. ...

- Enhanced security.

What information is excluded from a patient portal?

Which of the following forms of information are considered clinical information?

How do you implement a patient portal?

- Research different solutions. ...

- Look for the right features. ...

- Get buy-in from key stakeholders. ...

- Evaluate and enhance existing workflows. ...

- Develop an onboarding plan. ...

- Successful go-live. ...

- Seek out painless portal migration.

What is portal message?

How do you improve patient portals?

- Include information about the patient portal on your organization's website.

- Provide patients with an enrollment link before the initial visit to create a new account.

- Encourage team members to mention the patient portal when patients call to schedule appointments.

Why is patient portal important in healthcare?

What makes the patient portal different from a PHR?

How is health information exchange intended to improve care quality?

Overview

Patient portals improve the way in which patients and health care providers interact. A product of meaningful use requirements, they were mandated as a way to provide patients with timely access to their health care. Specifically, patient portals give patients access to their health information to take a more active role.

Primary Benefits

No matter the type of platform you choose, your patient portal can provide your patients with secure online access to their medical details and increase their engagement with your practice. And not to mention that it does so while providing several benefits for health care providers as well. Some of these benefits include:

Notable Challenges

While many people have used a patient portal by now, they have mixed reviews at best. As you can see in the section above, there are plenty of benefits that patient portals provide. But unfortunately, their potential has yet to be fully harnessed.

Emerging Trends

If patient portals are a mixed bag, why should the patient portal receive greater consideration in the EHR, EMR and practice management selection processes? Because when you look at current industry trends, patient portals are well on their way to improving. Some of these trends include:

How to Use a Patient Portal

With patient portals, the first and foremost thing you will need is a computer and a working internet connection. Create a customized user’s account in the software to avail medical services on your own. Once you enter the patient portal, click on links and products sold by the provider and tap into a new experience.

Solution Evaluation

Now that you know what a patient portal is and given the potential and growing importance, how should you evaluate the best portal for your practice or facility? You can select a standalone patient portal that a third-party vendor commonly hosts through the cloud as a health care provider.

Final Thoughts

It’s clear that using a patient portal software can provide several benefits for your medical practice. After accounting for these nine considerations, you should be ready to start using a patient portal. The only decision left to make is which platform you’ll use.

When did PHMG start patient portal?

PHMG launched the patient portal in early 2010. As a first step, the physician champion piloted the portal for about 6 months before it was implemented in one clinic at a time. According to the physician champion, implementation was “easier than expected because everyone was already comfortable with eClinicalWorks, ...

What are the challenges of the portal?

One major challenge with the portal is the multiple step registration process . Patients provide their e‐mail address at the front desk and are given a password to register from home. Some patients fail to complete the registration process after leaving the clinic. Remembering and managing passwords and managing family accounts are also challenging for patients. For example, a parent may log in for one child and then ask questions about a second child. For providers and staff, a challenge is that there is no way to know whether a Web‐enabled patient actually uses the portal and there are no read receipts to confirm that patients have read a message.

Why is PHMG monitoring?

Messaging is monitored periodically to ensure that communication with patients is succinct and user-friendly.

How many clinics does PHMG have?

PHMG is an independent medical group with 11 clinics in southwest Idaho, provides both appointment‐based and urgent care. PHMG has 46 health care providers (including 12 mid‐level providers) and averages 200,000 patient visits per year. About half of PHMG’s patients are appointment‐based and half are urgent care. The practice specializes in:

What is the PHMG strategy?

PHMG had a strategy of ensuring that patients hear about the portal from multiple sources during each clinical visit. To execute this strategy, PHMG used several methods of communication, including:

Why is it persuasive to use a portal?

They found that it is particularly persuasive when providers encourage patients to use the portal because patients trust providers and value their opinions. One provider says he reinforces a patient’s use of the portal by closing all messages with “Thanks for using the portal.”.

When did PHMG implement EHR?

In 2007 PHMG implemented an EHR system, eClinicalWorks, as part of a strategy to improve quality of care and facilitate coordination of care across its multiple clinic locations. In preparing for implementation, PHMG proceeded with:

How does patient portal help?

According to Clain and Moseley’s data, patient portals improve revenue cycle management by allowing patients to pay their medical bills online. As a result, practices receive payment faster, in fuller amounts, and at a higher frequency. Online bill pay not only benefits practices financially, but helps improve patient satisfaction rates.

Why are patient portals important?

Patient portals have more tactical uses for improving patient loyalty. By enabling communications regarding health ailments, providers can call the patient back into the office if need be.

Why do providers need to implement patient engagement strategies?

As risk-based payment models such as accountable care organizations gain industry popularity, providers need to implement patient engagement strategies not only to deliver quality care, but to ensure that their revenue cycles can benefit from adopting these new techniques.

Does self scheduling help with patient loyalty?

Self-scheduling functions also play a considerable part in boosting patient loyalty rates. According to Moseley and Clain, patients tend to prefer online scheduling of appointments over phone scheduling. If a practice offers online scheduling, patients are more likely to stick with that practice than find another one.

Does the patient portal drive adoption?

The pair stated that effective use of the patient portal will drive adoption rates. According to some of Moseley’s research, providers with high portal adoption rates also have the highest portal engagement rates.

Why are patient portals important?

While the evidence is currently immature, patient portals have demonstrated benefit by enabling the discovery of medical errors, improving adherence to medications, and providing patient-provider communication, etc. High-quality studies are needed to fully understand, improve, and evaluate their impact.

What are the inputs and outputs of a patient portal?

The inputs are the material (eg, hardware and software) and nonmaterial (eg, leadership) components that facilitate or impair the establishment or use of the portal. Processes include the interactions of the users with the portal. Outputs comprise the results of the implementation or the use of the portal. Through the analysis, we identified 14 themes within these three categories, shown in Textbox 1.

How does patient involvement improve quality of care?

Promoting patient involvement in health care delivery may lead to improved quality and safety of care [14,15] by enabling patients to spot and report errors in EMRs, for example [6]. Some patients recognize the role of patient portals in their health care, reporting satisfaction with the ability to communicate with their health care teams and perform tasks such as requesting prescription refills conveniently [3,16]. Portal use may reduce in-person visits, visits to emergency departments, and patient-provider telephone conversations [3,8-10,12,16]. Despite the potential of portals, already used in the ambulatory setting for some time, implementation in the inpatient setting has only recently gathered momentum [17-19]. The inpatient setting presents additional challenges for implementing patient portals [18,20]. Clinical conditions leading to hospitalization are often acute and the amount of medical information generated during this time can be extensive, which may overwhelm patients [20] and challenge information technology to rapidly display this information.

How many articles are in the systematic search?

The systematic search identified 58 articles for inclusion. The inputs category was addressed by 40 articles, while the processes and outputs categories were addressed by 36 and 46 articles, respectively: 47 articles addressed multiple themes across the three categories, and 11 addressed only a single theme. Nineteen articles had high- to very high-quality, 21 had medium quality, and 18 had low- to very low-quality. Findings in the inputs category showed wide-ranging portal designs; patients’ privacy concerns and lack of encouragement from providers were among portal adoption barriers while information access and patient-provider communication were among facilitators. Several methods were used to train portal users with varying success. In the processes category, sociodemographic characteristics and medical conditions of patients were predictors of portal use; some patients wanted unlimited access to their EMRs, personalized health education, and nonclinical information; and patients were keen to use portals for communicating with their health care teams. In the outputs category, some but not all studies found patient portals improved patient engagement; patients perceived some portal functions as inadequate but others as useful; patients and staff thought portals may improve patient care but could cause anxiety in some patients; and portals improved patient safety, adherence to medications, and patient-provider communication but had no impact on objective health outcomes.

How does a patient portal improve patient engagement?

Patient portals may enhance patient engagement by enabling patients to access their electronic medical records (EMRs) and facilitating secure patient-provider communication.

What are organizational factors in healthcare?

Organizational factors: culture of a health care organization; decisions and actions it takes when an initial consideration is made to implement a patient portal

What is portal design?

Portal design: umbrella term for all design-related aspects of the portal including portal interface, content, features, and functions

How many patients have access to a patient portal?

In May 2019, we surveyed 232 patients and found that 72% had access to a patient portal. That’s an approximately 64% increase over the finding concluded in a similar study conducted in 2016.

What to do when your practice is ready for patient portal?

Once your practice is ready for new patient portal software, take some time to consider what functionality is on your wish list. The range and breadth of features a portal offers will vary based on vendor and cost.

Why do we need portals?

Other reasons to implement a portal include: To foster better patient-physician relationships: Portals offer a round-the-clock platform on which both parties can conveniently exchange health information, ask questions, and review medical notes—providing more opportunities to connect.

How to request a prescription refill?

Highlight: There are two different ways to request a prescription refill through this portal: click on the “request refill” button on the home page, or go to a separate “Refill Requests” page to view a comprehensive list of current medications and make a specific selection.

Can a patient portal be integrated into an EHR?

It’s very common for patient portals to be bundled into an integrated EHR suite that includes additional medical software applications. Alternatively, practices can choose to purchase patient portal software as a stand-alone or integrated program. Here are the differences between the two types of systems:

Does a portal success come down to whether or not patients actually use it?

Even after you’ve done everything we’ve suggested for a smooth portal implementation, its success will ultimately come down to whether or not your patients actually use it.

Where is the balance due amount on a patient's invoice?

Highlight: The patient’s invoice, with the balance due amount emphasized in red text, is located right above the billing information form for easy reference.

How does a patient portal affect health care?

This can be affected by multiple factors at the micro (eg, “individuals”), meso (eg, “re sources”), and macro (eg, “sociopolitical context”) levels [21]. Several implementation models are available, such as “The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR),” which is used in many studies as a guiding framework [22-24]. CFIR consists of 5 levels at which barriers and facilitators can occur during implementation: (1) technology-related factors (eg, “adaptability,” “complexity,” and “cost”); (2) outer setting (eg, “policy and incentives”); (3) inner setting (eg, “resources”); (4) process (eg, “engagement of stakeholders”); and (5) individual health professionals (eg, “individual’s knowledge”). In this model, patients are part of the “outer setting,” suggesting that the CFIR framework is aimed primarily at institutions [24]. Another example is the “Fit between Individuals, Tasks, and Technology” (FITT) framework, which is aimed at the adoption of IT [25]. The comprehensive model of Grol and Wensing [26] summarizes the barriers to and facilitators of change in health care practice at 6 levels: (1) innovation; (2) individual professional; (3) patient; (4) social context; (5) organizational context; and (6) economic and political context. McGinn et al [21] argue that the consideration of various stakeholder opinions can contribute to successful implementations. However, previous research mainly focused on perceptions of single stakeholder groups regarding patient portal implementation, such as physicians [27] or nurses [28]. This highlights the importance of identifying the opinions of many stakeholders during patient portal implementation. Furthermore, it remains unclear which factors are important in accomplishing change in the various groups [26].

How long were the patient portal interviews?

All interviews were performed by telephone and lasted for, on average, 20 min. Participants were first asked for their consent to make audio recordings of the interviews. Then, the purpose of the interview was introduced, and subjects were asked if they received the introductory email. This email was then briefly discussed such that the subjects were aware of the topics to be discussed. After that, questions were asked about participants’ characteristics, such as their age and work experience. To make sure an unambiguous definition of a patient portal was used, participants were asked what their definition of a patient portal was, and if necessary, it was complemented with our definition. Then, we asked them about their perceived barriers to and facilitators of patient portal implementation at all 6 levels [26]. If necessary, for example, if the question was unclear, the interviewer provided examples (and these were also sent per email). At the end of the interview, the participants were asked to suggest additional topics or issues, if any, that had not yet been covered. The interviews were in Dutch, and the questions in Multimedia Appendix 1are translations.

Why is patient centeredness important?

Patient-centeredness is an important element of high-quality care: effective communication between patients and their health care professionals , and information access can both contribute considerably to this [1]. According to the Institute of Medicine, “patients should have unfettered access to their own medical information” [2] to support them in taking control of their health (eg, using medical information to make informed health-related decisions) [2]. Information technology (IT) can play an important role in improving access to this information [3], and it also improves the participation of patients in their own care [4]. In health care, an increasingly popular way to facilitate this is by using patient portals [5]. Patient portals can be defined as “applications which are designed to give the patient secure access to health information and allow secure methods for communication and information sharing” [6], as well as for administrative purposes [7], and are mostly provided by a single health care institution [6,8]. These portals are often connected to the electronic health record (EHR) of an institution—defined as tethered patient portals [9]—to provide access to patients’ medical information [3,10-12]. Some institutions allow patient portals to facilitate communication between patients and health care professionals [3,6,12], view their appointments and provide patient education [11,13], share information [12], request for repeat medication prescriptions [3], and provide tailored feedback [11,13]. Patient portals may have a range of functionalities that enable information exchange (such as having access to the EHR), which in turn may facilitate and improve the communication between the patient and the health care professional [11,14]. Previous research showed that patients are especially satisfied with access to information from the EHR and the list of their appointments [11]. Portal use can also have a positive effect on self-management of conditions [15-18], communication between patients and providers, quality of care [16,17] and participation in treatment [17]. Patient empowerment can also be improved; the accessibility of information can especially contribute to “patients’ knowledge” and their “perception of autonomy and being respected” [19]. On the other hand, effects on health outcomes are reported to be mixed [6]. In summary, patient portals can be important as they provide patients with access to their own medical information, enable interaction with their health care professionals [8], and aim to involve patients in their own care processes [1].

Is a patient portal a technical process?

Patient portal implementation is a complex process and is not only a technical process but also affects the organization and its staff. Barriers and facilitators occurred at various levels and differed among hospital types (eg, lack of accessibility) and stakeholder groups (eg, sufficient resources) in terms of several factors. Our findings underscore the importance of involving multiple stakeholders in portal implementations. We identified a set of barriers and facilitators that are likely to be useful in making strategic and efficient implementation plans.

What is Carepaths EHR?

CarePaths EHR is an online (ASP), integrated electronic medical record (EMR) and practice management (PM) system. It is designed for psychiatry, psychology, mental and behavioral health, and social services. Some of the CarePaths'... Read more

What is my client plus?

My Clients Plus is a cloud-based medical platform. It is used by mental and behavioral health providers for medical practice management. My Clients Plus’ key features comprise therapy billing, client portal, to-do list, thera... Read more

What is the role of patient access in the revenue cycle?

The Patient Access as a core function of the Revenue Cycle starts with registration, scheduling and all of its support processes to patients, providers, and payers throughout the patient’s healthcare experience. Its main function is to supply information which results in building the foundation for medical records, billing & collections.

What is the purpose of the patient access department?

Collection of Insurance Information: The patient access department provides the input of the patients’ insurance or payment information. They scan and store multiple insurance card images and maintain a complete history of patient’s past, present and future insurances. The patient’s financial responsibility is determined by gathering data about insurance coverage, additional insurance, and their maximum allowable visits.

What is iPatientCare?

iPatientCare is a leading healthcare technology company providing Cloud-based Unified System integrating EHR, PMS and RCM technology enhancing patient care through care management/coordination/analytics, and reducing costs of care delivery At iPatientCare, we help clients address today’s evolving Patient Access needs. As a single source, we can create standardization and accountability across all of your revenue cycle operations.

What is a point of service collection?

Point of Service Collections: Here the patient access personnel collect co-pays and deductibles at the time of service. Services that require co-pay, and the predetermined amount payable for each service, is specified to the patients. Many patients appreciate knowing in advance of service what their portion of the bill will be. This gives them time to prepare or to make arrangements for the payment.

What is the benefit of synchronizing the revenue cycle?

Greater synchronization of the different aspects of the revenue cycle will only increase the likelihood of reimbursement delivery, improve patient communication, and make sure high-quality care delivery is the ultimate result.

What is a patient self check in kiosk?

Patient Self Check-in Kiosk: Patient kiosk is tabloid and a phone-based software application that assists patients to do self check-in and also edit their basic demographic details. Patient kiosks can be considered as the new step taken to streamline and simplify the patient registration procedure. This Patient Self Check-in Kiosk frees the front desk from manual data entry tasks and allows them to utilize their time productively.

What is the purpose of registration?

Registration: Registration is the first interface that the patient has with the health facility. In addition to validating demographic and insurance information other mandated fields are captured during patient registration. This information serves as the foundation of the patient’s medical record. The data collected is utilized by multiple members across the healthcare team, to include Patient Accounts, Patient Information, Clinicians and Health Information Management.